Visual design for researchers: a crash course

A whimbrel with a nice little stained glass pattern behind him. This little piece shows off a couple of principles, particularly off-center focal points and diagonal motion, that I’ll break down here.

Science Twitter has several conversations that tend to repeat themselves. Some are on a frequent cycle- say, the 80-hour work week, or email etiquette. Others take their time to come back around again, and this week saw the first time in a couple of years that the Poster Design Discourse took over the feed. As someone who literally does scientific illustration as what seems to be morphing into a bona fide second job, I obviously have thoughts on this, and maybe I’ll do a poster design post at some point. But it also highlighted that research- particularly communicating our research- requires so many skill sets that most of us have absolutely no formal training in, and visual design is absolutely one of these.

I’m lucky in this regard. I come from a family that, except for me, all make their livings in the arts. I attended an arts magnet school from 7-12 grade, competing in both local and national art contests. I paid for my first semester’s textbooks with my Scholastic Art award scholarships, and even while I followed the path of hard-core science-nerddom, I never lost my roots as an artist. That formal training, as long ago as it was, has served me well as I try to find the best ways to communicate and share my research with a range of audiences.

So while I’m certainly not a trained art instructor, I do get asked a lot about how I make my illustrations and figures, and what lessons I have for others. As with any time I get asked my thoughts on a topic repeatedly, I figured that it was probably time to sit down and compile it all into a guide that would be more widely accessible. I’ll focus on general principles of visual design here that can be applied to anything from figures for a paper to a poster or presentation, without necessarily focusing on a single application.

Principle 1: The best tool for the job is the one you feel most comfortable using

The first thing I usually get asked about my art is “what program do you use?”. In fact, the tweet that sparked the conversation this post is a part of was one that mocked people for using Powerpoint to make posters. Artists often have strong opinions about their preferred medium— I, for instance, have preferred brands for most of the acrylic pigments I use, and get very perturbed if the Utrecht cerulean I like is out of stock and I have to get the Windsor and Newton one, even though I prefer the latter for ultramarine.

But there’s a difference between those conversations when you are doing art on a professional or even just large-scale hobby, and when you’re doing a handful of figures for papers or a single poster every year. While learning how to use a dedicated tool or a more advanced art program is immensely rewarding, I actually don’t think it’s necessary for many researchers. Even for my preferred art program, I chose it not because of weighing the benefits or anything, but because my university didn’t offer free Adobe subscriptions and my PI decided to get a Sketch license for the lab instead. I could switch now, but honestly? I’m comfortable with Sketch and I don’t see a compelling reason to switch.

So, don’t sweat it too much on what program you decide to use. Powerpoint has become increasingly powerful and sophisticated in recent years, and can be used to make absolutely gorgeous figures. MS Paint is another option that is overlooked, and has some solid features. Google Slides is good if you have multiple collaborators working on a poster. Anyone who shames you for that owes you a training session in whatever program they’re trying to sell you on.

Principle 2: Use your space thoughtfully

Here’s where we’re going to go through some vocabulary terms to introduce some ideas on how you use the space you have to work with. The visual window— the bounded space you’re going to create your image in— is generally broken into two categories of space, which you might have heard of: positive space and negative space. Simply put, positive space is “stuff”; negative space is “where you put the stuff”, either the background you create, or, often in scientific figures, space that is intentionally left blank. However, “empty” does not mean “unimportant, as this example nicely demonstrates:

Figure from my 2020 Molecular Ecology paper, with the positive space marked in purple and negative indicated by the green caption.

In this example, a lot of the space seems empty, but both the positive and negative spaces are telling equal parts of the story. Our eye is drawn to the negative space between the two groups of points as much as to the points themselves. This gap is actually a key finding of this paper, which looked at divergence in Beringian birds and found that taxa tended to either be highly diverged with little migration, or highly introgressed with little divergence, with no intermediate outcomes. That bit of negative space drives that point home.

Okay, so we have these general types of space. Let’s break down more about how the objects in our space are arranged. Often, the default is to arrange each component in its own space, for clarity. This is sometimes necessary, like in this example here:

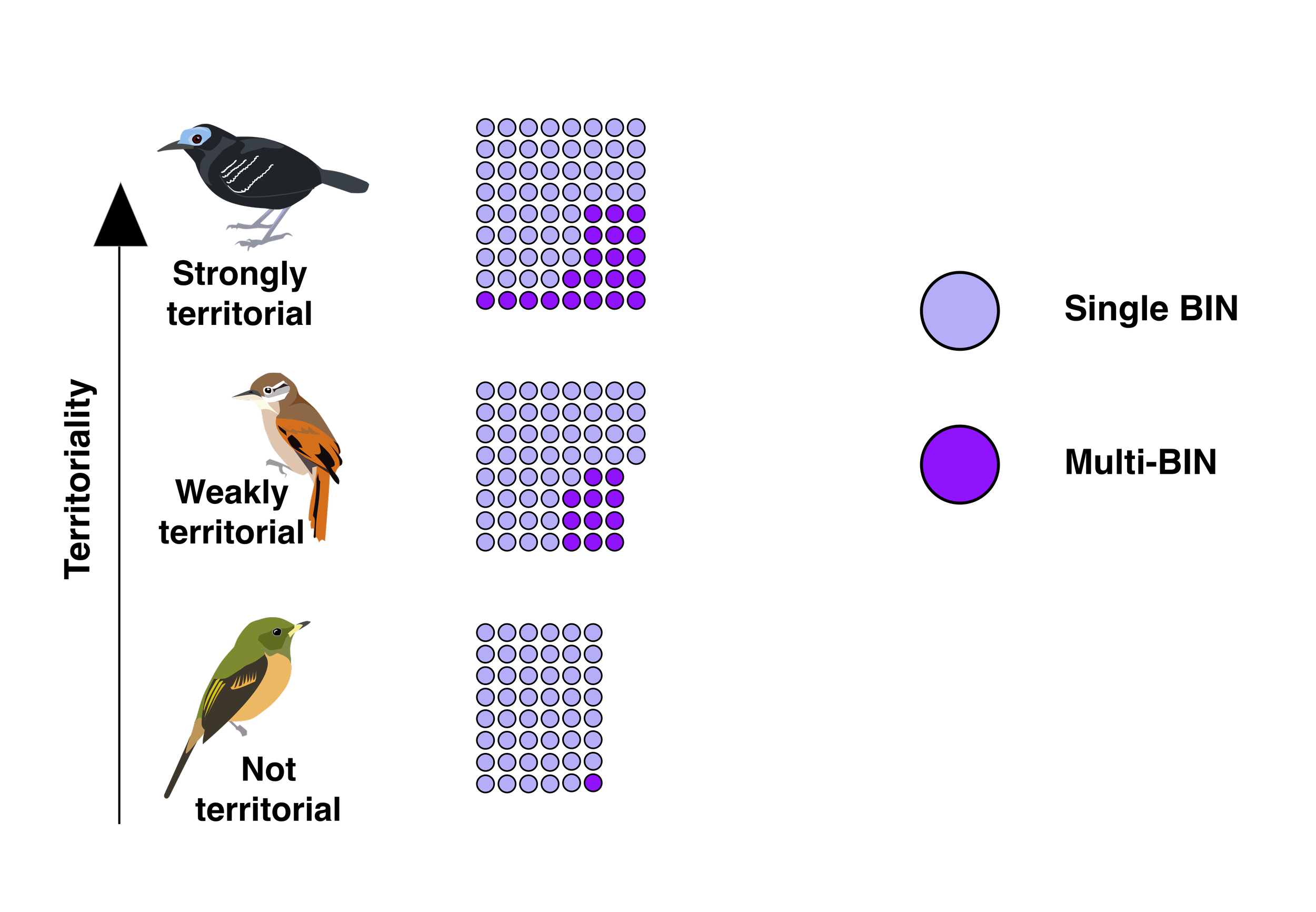

A graphic from my dissertation work, with individual birds, text, and dots representing species all discretely positioned without any overlap.

But while this is sometimes necessary, these figures can feel very abstract and static. Let’s look at a different figure here, a map of different hummingbird ranges:

A map of western South America where individual hummingbirds are superimposed over color-coded circles, overlapping with the political boundaries of the map.

Notice how different components overlap? This is a principle called interaction of objects, where individual pieces of the composition are allowed to overlap and be more strongly spatially associated with each other. This is one of those things that human brains tend to like, probably because it suggests space, and so we tend to find images with it particularly appealing. It also can help link different elements more firmly in the mind of the viewer. In this case, the colorful circles behind each bird reinforces the color-coding used throughout that particular paper.

Interaction of objects is visually appealing because it works with our unconscious expectations of how objects work in 3D space. The final term I want to introduce you to works because it breaks expected visual rhythms. Most of the time, we arrange things to align either vertically or horizontally. Again, in many cases this is the best way to go, and in figures in particular is something that you don’t necessarily have control over. But breaking up a composition with diagonal motion— ie, arranging components along a diagonal vector, not a strict vertical or horizontal— is an important tool to use, especially for things more like poster design:

Poster design for a PhD defense. Notice the multiple diagonal elements- the phylogenies rotated to a 45 degree angle, the map of the islands in the opposite direction, and even the tails of the ‘elepaio drawings on the top.

These are just a few basic concepts, but learning how to use them can help bring a composition some extra motion while conveying information more efficiently.

Principle 3: Think about color

Coming up with a striking color scheme can be one of the most satisfying parts of design, but it’s also one of the more intimidating. How can you make things pop without being too busy, while also being color-blind friendly? What colors work well together? It can all be a bit much.

Let’s take a look at a color wheel:

A stock color wheel. There’s lot of versions, but in this particular one, each color (a hue, if you’re being fancy about it) is shown with two tints (lighter versions) and two shades (darker versions) bracketing it. A combination of hues, tints, and shades is key to eye-catching and appealing visual design.

Many folks know that we generally classify greens, blues, and purples, as cool colors, and reds, oranges, and yellows as warm. Picking colors within those groups can be one way to make a color palette that matches well. Alternately, we can go with complementary colors— warm and cool colors that pair well together, and are across the color wheel from each other. In the wheel above, for instance, azure (a medium light blue) is across from wheel from buff, turmeric, yellow ochre, tan, and milk chocolate, all of which are potentially good matches. Yellow ochre, at the same ring of the circle, is the direct complement, but the tints and shades— the variations of that color created by lightening or darkening it, respectively— are also good choices, with the added benefit that of being more likely to be distinguished from azure if reproduced in monochrome or by someone with yellow-blue colorblindness.

In general, simpler palettes are better, and I recommend choosing between 3-6 colors in most cases. The black lines and text and any pictures or photos you need to include in some figures don’t count towards this, in case you’re wondering. While sometimes it’s unavoidable— looking at you, most PCA plots— choosing a simple palette and keeping it consistent throughout your paper or talk will maximize visual impact and not imply any extra information that doesn’t exist (as in “wait, now there’s purple points, what do those mean?”).

Let’s quickly go back to one of the things I mentioned there in passing. Sometimes you need to include actual photos or other pictures in figures, and it would be nice to make everything coordinate. Luckily, there’s a simple tool available in many programs to allow you to pull colors directly from an image so you can use it to build a palette: the eyedropper tool:

Screenshot of the eyedropper tool in action. In this case, it’s in Sketch, but it’s also available in Powerpoint, MS Paint, and many other programs. With it selected, you can easily move your cursor over an image— say, a nice sunset on Lake Victoria— to select specific colors from it.

Decide how many colors you need— in this case, I went with five— and use the eyedropper to sample various parts of the picture until you get a combination you like. You can then use either those exact selections if you’re in the program you’re using for illustration, or plug the hex value or RGB values, both available on the color menu to the right, into the R code or whatever of your choice.

There’s also a rich variety of color palettes, usually organized around specific themes, that folks have generated for use with R. There’s bajillions to choose from, and many have already been tested to be colorblind-friendly. Here’s a few suggestions:

A tried-and-true suggestion, MetBrewer is based on art from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Hiroshige palette was actually the starting point for the defense poster included in this post.

Jake Lawlor has a gorgeous set of Pacific Northwest-inspired palettes available at PNWColors.

I may have some objections to the claim that the inspiration for this package, teleost fishes, are “nature’s most stunning and colorful organisms” (hello, hummingbirds and nudibranchs would like a word, lol) but the fishualize package is undoubtedly an absolutely stunning collection, and undoubtedly a top-shelf pun.

Want to have a little nerdy easter egg in your figures? PokePalettes and PaletteTown provide palettes based on the Pokemon of your choice, the latter as a handy R package.

As you may have guessed, I love a good retro screen print, especially the National Parks series of WPA reproductions and WPA-inspired modern prints. NationalParkColors puts these palettes in a neat little package.

Need some inspiration from the big screen? Wesanderson, ghibli, and ggsci have you covered— the first two are self-explanatory, the last takes inspiration from, among other sources, sci-fi movies and TV.

They may not have a cute hook like some of these others, but ColorBrewer, ColorBrewer 2, microshades, khroma, and viridis all provide huge selections of palettes optimized for accessibility for multiple types of colorblindness.

This is literally just a tiny portion of what’s out there. When I asked on Twitter, I immediately got tons of responses, and there’s no way I could include them all. Additionally, check out this and this for more thoughts on color choices in figures.

One best-practice I urge you to do: always double-check your figures for colorblindness compatibility, especially for custom-generated palettes. Even a colorblind-friendly palette may lead to weird results sometimes depending on the frequency and placement of the colors, so it’s always best to double-check. Tools like ColorBlindr can help make sure your beautiful images are as accessible as possible.

Principle 4: Relax and have fun

You won’t be perfect at this right away. That’s absolutely normal, and try not to let the fear of that keep you from experimenting and trying new things. You will have to redo figures. You will have to try multiple color schemes. You will have to rearrange things and workshop designs and just generally fidget with things until they look right. Try not to take any of those failures personally, and be open to critique. And if you find some aspect of visual design really speaks to you, lean into it! You may find a skill or passion you didn’t know you had :)